At SendCutSend’s manufacturing facility in Reno, CEO Jim Belosic discusses a part with a co-worker. (Image courtesy SendCutSend)

From prototypes to production runs of 50,000 parts or more, SendCutSend makes manufacturing accessible to all.

By Mark Shortt

In 2018, Jim Belosic was a manufacturing hobbyist with a software background. The more he pursued his hobby, the more he realized he needed to outsource some of his work. That’s when he experienced a major roadblock: The companies that could help him manufacture parts weren’t interested in making just one part. Instead, they required minimum quantities at prices he wasn’t willing to pay.

Frustrated, Belosic decided to combine his prowess in software with his passion for fabrication. He and his software firm’s CTO, Jacob Graham, started SendCutSend with a goal of making manufacturing more accessible to people who weren’t trying to manufacture large quantities of parts. They would do it with software, crafting an automated process that enables anyone—from hobbyists to OEMs—to source manufactured parts through an Amazon-style service.

Today, with manufacturing facilities at its headquarters in Reno, Nevada, and in Paris, Kentucky, SendCutSend employs about 150 people. Small manufacturers and large manufacturers comprise 95 percent of the company’s business, yet hobbyists and the average maker are always welcome to use its service. Meanwhile, SendCutSend finds itself on the annual Inc. 5000 list, breaking in at number 339. The company’s revenues have reportedly grown more than 1,600 percent over the last three years.

SendCutSend CEO Jim Belosic spoke recently with Design-2-Part about the custom, on-demand manufacturing capabilities of SendCutSend, including how the company got started, its current niche in the manufacturing industry, and its goals for the future. He also discussed the advantages that he believes SendCutSend offers through its processes and services, versus other companies that may provide similar services for rapid manufacturing or custom manufacturing.

Following is our conversation, edited for brevity and clarity.

Design-2-Part: How did SendCutSend got started? What made you decide to go into this business?

Jim Belosic: I started out in marketing. In 2002, I was working out of my kitchen, doing marketing and creating graphics for newspapers. People would say to me, ‘I need a website. Can you figure out how to build a website?’ So, I would go and try to figure out how to build websites. I got pretty decent at it, and started to grow a little team. And then they would ask, ‘Okay, you built my website. Can you build me a reservation system? Or ‘Can you build me an online store?’ So, that’s when you start to go from marketing to software development.

Fast forward to 2012. We became a full software development agency, and we had a couple of products that were very successful. The world of software was super cool—it’s problem solving—constant problem solving, all the time. You just are using a keyboard instead of your hands.

But I’ve always been a fabricator and welder and car guy, someone who likes to work with my hands. So when we’d have downtime at the software company, my CTO and a couple of other guys would go and work on [fabrication] projects. As the years went by, I found myself wanting to work on projects more than software. The projects got more and more elaborate, and I started needing to outsource work. I had a CNC plasma table that I owned, and some welders, but every once in a while, I’d need parts made. That’s when I discovered that, when trying to get parts made, people didn’t want to make one part—they wanted to make a thousand, or they wanted to do it for some ridiculous price.

Being a software guy, I realized we could write software to make this easier. Let’s enable all of these legacy manufacturers to use our software so that they can take a hundred customers, put them on one sheet, sort it out, and make it really profitable, but then still accessible to all these hobbyists.

So, my CTO, Jacob Graham, and I built some trial software. Our original intent was to sell it to the industry. However, when we started to shop it around, we realized that there wasn’t a lot of uptake because people liked doing things the way they did them. They liked looking at the prints, they liked having design engineers look over the design and do all of their DFM checks manually.

We realized that in order to make this work, we’d have to buy our own equipment. So we did. I

bought a laser, and then, combined with our software and our process, we were able to start SendCutSend, where people just upload their design to us, we manufacture it, and send it right back to their door. So, the business definitely started as a selfish need to make sure that I had access to manufacturing, even though I wasn’t an OEM or a guy doing a huge volume of parts.

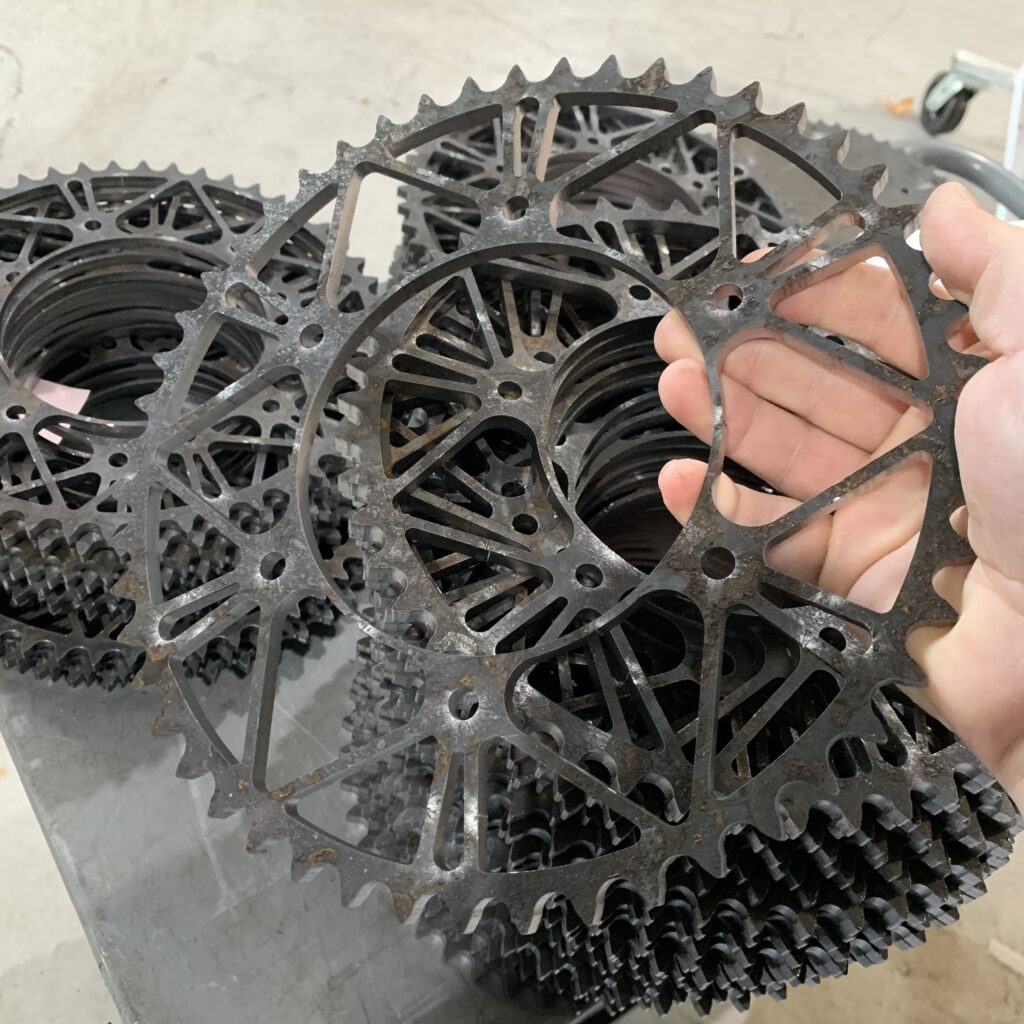

Gears manufactured by SendCutSend. (Image courtesy SendCutSend)

D2P: Could you give an overview of how SendCutSend’s process works, from the time a customer submits their CAD design, through to the delivery of the completed part?

JB: The first thing that we ask is that your design has to meet some of our requirements. We can’t make every single file type work, but we do our best. We accept all of the standards—DFX, .dwg, STEP files.

Once they’re uploaded, we instantly run a bunch of manufacturability checks—DFM checks. We’re running a hundred to 200 different checks on the file to make sure that the part is actually manufacturable. In some cases, we do instant fixes—we remove duplicate lines, or if there are entities that aren’t perfectly closed, we’ll close them. Once we know the geometry is manufacturable, we’ll say, ‘Let’s go ahead and choose the material.’ Because we’re in the quick turn business, we stock every material. So, we give the customers a selection of material to choose from, and then we run more DFM checks.

If they have something like a dragonfly wing design, but they want it in half-inch steel, and it’s really small, we’ll warn them that it might not be manufacturable in that type of material because the geometry is too tight, or it’s going to burn out, or whatever.

So we run a second set of DFM checks, and at the same time, we’re calculating price. We’re understanding the material usage, scrap, cut inches, the pierce time, the consumable usage, labor. We run hundreds of different factors in order to calculate price, and then display that in real time to the customer so they can decide if they want to continue with the purchase or not.

Once they’ve decided to continue with the purchase, we take their credit card information, and the sale is complete. At that point, it becomes a job in our system, and we nest it. We’ll take the part, and we’ll dig it up with everyone else who’s selected that material that’s waiting in the queue, in order to get the best material utilization. Again, we’re running algorithms to decide: Are we behind schedule and we need to cut it now? Or are we ahead of schedule and we can wait a little bit and try to make that nest yield a little bit more? Are there other processes downstream that are going to force us to cut this faster or slower? What’s our material on hand? What’s our labor on hand? So we calculate all that, and then we show them a lead time.

Once it goes out onto the floor, it’s relatively automated. It’s going to go onto one of our primary pieces of equipment. We use Amada lasers, from 4kW to 12 kW. We also have CNC routers and waterjets. So, depending on the material, we’ll choose how we’re going to cut it.

After the material is cut, the job goes into a tote, where it gets QC checked, at every single process, for quality and accuracy. If it’s going to be bent or deburred, or it’s going to have PEM hardware inserted, or anodizing, our software guides it through our entire system. At the same time, we’re updating the customer, in real time, of the status of their order. We’ll say, ‘It’s been cut, now it’s going to deburring; it’s been deburred, now it’s going to go to bending; it’s been bent, now it’s going to final QC; and then, ‘It’s been shipped, and here’s your tracking number.’

So it’s boxed up, and then to your door in usually two or three days of transit, because we have a facility in Reno, Nevada, and a facility in Paris, Kentucky, so we can reach both ends of the country relatively quickly.

D2P: When a customer submits their CAD file, are there ever any situations where you might let them know of a better way, a better process to manufacture their part, versus the one that they thought was the right process?

JB: Yes. Often, we’re able to catch it before production. In the worst case, we catch it during production. In both cases, we will reach out and offer recommendations.

We are very heavy on the support side and application engineering side because many of our customers are not engineers. Maybe this is their first time using CAD, so we offer a lot of hand holding. But in the end, it pays off because they’re just excited to see that they can use a computer in order to hold a real part in their hand. Once they break that seal, they become lifetime customers.

D2P: For what types of parts manufacturing needs does your process offers the best solution for your customers?

JB: If you need a very high quality part very quickly, that’s where we really shine. We find that because we’re able to task such a short lead time, people can order in smaller batches, and actually have more variation or iteration of their product as time goes on.

The way our pricing is set up, you don’t need to order 100,000 things to get the absolute best deal. You might be able to order a thousand at a time. What we see is people are making iterations every batch, and by the time we do the 10th batch, the part is becoming so much better. The customer is learning how to save costs, or they’re learning how to make it more reliable, for example. Those are really our favorite projects—projects that can have lots of iteration over their lifespan.

D2P: What would you say is the key that allows you to do custom work so well for your customers?

JB: It’s definitely a mix of our in-house software and our process. We don’t use any ERP system or warehouse management system, or anything like that—we built our own. And because we were able to build it from scratch, very specifically to our process, it gives us a huge advantage. Our system is designed to handle extremely high mix, extremely low volume [projects] on a day to day basis, without hiccups, and it’s still continuing to get better.

It’s been five years that we’ve been doing this, and it’s kind of unrecognizable from the first days because of the amount of complexity that we’ve had to build in. We always joke about how easy our job would be if we just made the same thing every day. I definitely give credit to our software and our processes that keep evolving.

D2P: Were you looking to concentrate on custom work when you started the business?

JB: Yes. We never went into this thinking that we were going to be a high volume, low mix manufacturer. We never really looked at the kind of equipment that you need for high production—stamping and forming and casting equipment. We are looking towards some of that in the future because we do have a lot of demand for high volume parts. But when we started, we knew that doing custom work was going to be our bread and butter, so that forced us to become good at it.

D2P: One of the ways that companies try to get customized parts is through 3D printing, but it’s not the only way. Do you have any plans to offer 3D printing at some point?

JB: Yes, possibly. We’ve been watching 3D printing for the last 10 years, and there are a lot of companies that are doing it really well right now. I also feel like we’re at a ‘VHS versus Betamax’ crossroads, where there are so many competing technologies and so many manufacturers. It makes me nervous to choose a technology because there’s a very high risk that it’s going to be obsolete in a couple of years.

But yet I still think that there’s so much potential in ‘boring old sheet and plate.’ Sheet metal has been around forever. It’s unsexy and hasn’t gotten a lot of attention, but it really makes the world work. Everywhere you go, there’s sheet metal and a little bracket in something. And it’s still definitely more cost effective to make a part out of sheet metal than to 3D print it. So, we’ll always have some demands, no matter how good 3D printing gets.

And as CAD systems get better and better, designers are able to get more and more clever with how they’re using sheet metal. We’ll see parts almost on a daily basis that used to be four parts that were welded together. But now, designers are getting really clever with forming and bending, where they can do this in one piece, as sheet metal, for a tenth of the cost—100 times faster. It’s really cool to see how that’s evolving. I attribute most of it to advances in CAD software.

D2P: Your company offers processes from laser cutting to waterjet cutting, bending and forming, and quite a few others. Which processes are most in demand?

JB: Laser cutting is our most in demand because we cut all of our metals with laser. We cut our composites with waterjet—so, carbon fiber, G-10, materials like that, we cut with waterjet. But laser is definitely the biggest chunk of our menu. And after laser cutting, I would say the biggest in demand is bending.

D2P: What advantages do you offer through your process and services, versus other companies that may provide similar services for rapid manufacturing or custom manufacturing?

JB: Just in general, it’s our accessibility. Because we built our business around people who are just getting started in manufacturing, it allows us to support people who are new, but then it allows us to support people who are experts even better. Our support staff, our engineering staff, is amazing. I don’t think anyone has invested as much in support and feedback and DFM and just going the extra mile to help them get their parts right and to help them get their project to completion. At the end of the day, we’re not making parts, we’re helping people finish projects.

People care about getting their project done. So that’s really our culture.

D2P: Many U.S. manufacturers are working to reduce their supply chain risks by sourcing domestically and making their supply chains more resilient. In light of the supply chain disruptions that have been occurring in recent years, what advantages does SendCutSend offer to U.S. manufacturers who are trying to reduce their supply chain risks?

JB: We’ve actually had hundreds of companies come to us and go, ‘Oh my God, I didn’t realize I could get it [the part] at this price in the U.S.’ And I attribute much of that to our automation and our software. We don’t need a massive staff of sales engineers or people who are just chasing down quotes. We do it all automatically, so we can keep our prices down.

The other thing is, because we are 100 percent U.S. based, we use U.S.-made steel, we use U.S. aluminum, we use U.S.-made equipment. Our equipment is made in Brea, California, and we can get parts instantly. That gives us a lot of isolation from supply chain events, so we’ve become a very reliable partner for our customers. We even have our own internal load balancing, where we can shift orders, or parts of orders, between Paris, Kentucky, and Reno, Nevada, if needed. We have redundancies in place as far as equipment and software and power systems—all kinds of stuff. So, when it comes to resilience, we’re really proud of it, and we’re proud to be able to do it in the U.S.

But I think we’re going to be seeing our story repeated many, many more times as technology becomes more advanced, as there’s more great American manufacturers that are getting their feet under them because people aren’t offshoring much more.

D2P: How would you like to see your company develop going forward? What are your goals for its development?

JB: Our goal is to be a partner with our customers, so I want to make sure that if you can dream it, we can make it. That’s kind of our long term goal. Even if you don’t know how to use CAD, we can still get that part made for you.

W just started a new service, called Design Service. You can send us a cardboard template, you can send us a dimensioned sketch, and we’ll work with you in order to make that a real part. I’d like to see that go farther. We’re limited to sheet and plate right now. But could we do 3D printing, or could we do injection molding, or stamping? No matter what you need, could we produce it? That’s the long term dream. It’ll take us a little while.