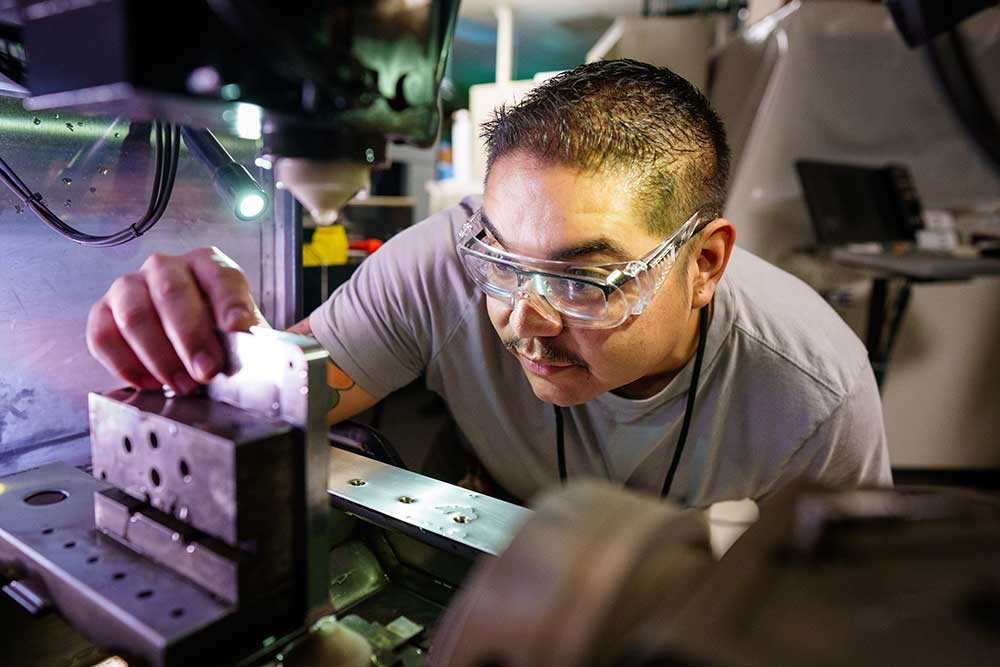

A Sandia machinist sets up 3D-printed metal parts for a newly designed cable connector used for testing the W80-4. The new connector is the result of collaboration across the Labs. (Photo by Craig Fritz)

Risk-taking leads to big results

By Kenny Vigil | Sandia National Laboratories

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M.—Robert Petterborg saw an opportunity to improve a critical part used to test a deterrence system. Using his spare time at work and with the help of his Sandia colleagues, he designed a new cable connector that eliminates misalignments that could interfere with testing and potentially damage hardware.

“I wasn’t assigned this work. This was a multifaceted and multidisciplinary project that I voluntarily took on to address a problem,” said Petterborg, who is a systems engineer and oversees several product realization teams for deterrence systems. “If everyone did things the way we’ve always done them, we wouldn’t have innovation. We would never have anything better than what we have now.”

Using 3D printing, or additive manufacturing, Robert designed a cable connector used to test the W80-4.

“My role is not to be a design engineer. This was unorthodox and a risk to do something out of the norm. I knew I had the capability, and Sandia has the diverse resources to make it happen. I took the risk knowing it had a high likelihood of success,” said Petterborg, who has previous design experience with test systems, lithium batteries, and solar and renewable energy.

With the support of his management and the help and input of many others at Sandia, he designed the new connector in about a year and a half. Without using 3D printing and model-based design, Petterborg estimates it could have taken a dedicated team three to five years to develop the connector.

“This new connector will eliminate bad connections, which means a reduction in the number of retests performed at Pantex (Plant),” Petterborg said. “Having a good electrical connection means high reliability and higher confidence in our stockpile.”

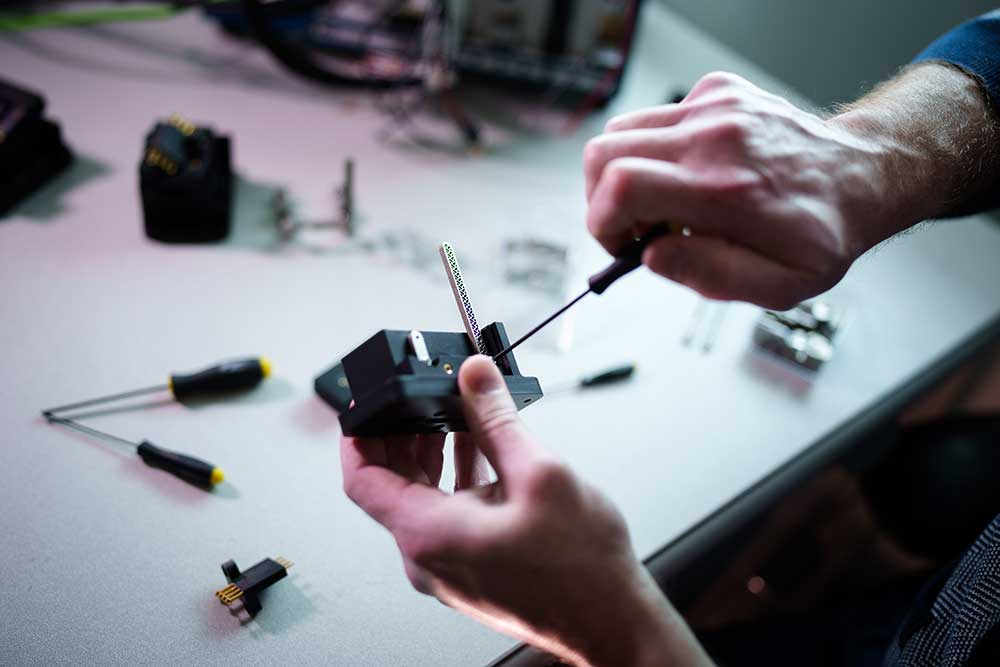

The newly designed cable connector, shown here being assembled by Petterborg, is simple to use—so simple, Petterborg said, it’s impossible to use incorrectly. (Photo by Craig Fritz)

Gathering user input

In addition to preventing poor connections, the new connector reduces the chance of potentially damaging cables and their assemblies. Cables are difficult and costly to manufacture.

“We’re very careful with how we handle cables and how they get assembled into products,” said Michelle Pang, a human factors engineer who worked with Petterborg on the newly designed connector.

Pang talked to engineers and operators who use the original connector and gathered information about what made it challenging to use. She then shared prototypes of the new connector.

“They provided a lot of positive feedback that contributed to how we got to this final component,” Pang said.

Sandia systems engineer Robert Petterborg assembles a newly designed cable connector in his office. Petterborg designed the cable in his spare time with the help of colleagues across the Labs. (Photo by Craig Fritz)

More user-friendly connector

The newly designed connector has a transparent window at the top, an opening on the side to slide in the cable, and a single lever that moves the parts of the connector.

“The window allows the user to visually align the cable in the adapter and then make a reliable, repeatable connection by lowering the lever. The lever has hard stops that prevent the user from lowering it too far or pushing it back too high,” Petterborg said. “When considering things that could impact how we build and test our stockpile, simplicity and reliability are paramount.”

The previous connector had many individual pieces, creating a risk of either a poor connection or damaging the cable.

“Instead of having multiple pieces that need to be assembled in the correct order, you’re now working with just one unit. It takes that guesswork out of whether you have a good connection and eases testing,” Pang said.

The production technicians at Pantex, where deterrence systems are assembled, have also tested the newly designed connector. Robert said they provided positive feedback about how easy it is to use.

Rapid fabrication

To make the connector, Petterborg turned to many other groups, including Sandia’s Rapid Development Connector team, led out of Connectors and Lightning Arrestor Connectors, in collaboration with Material, Physical, and Chemical Sciences and the Advanced Materials Laboratory.

The Rapid Development Connector team tested a variety of materials for the connector and rapidly fabricated multiple design iterations, saving time and money.

“Our team worked through multiple designs with Robert, and we were able to turn around parts for testing in weeks, sometimes even days,” said Michael Gallegos, the staff member leading the Rapid Development Connector project at the Advanced Materials Lab. “Having a direct line of communication with the people involved in operating the tools and assembling the parts helps provide the best engineering solution.”

Without the Advanced Materials Lab, Petterborg would have sent his designs to an outside manufacturer to be produced, taking anywhere from three to six months for each iteration of prototyping.

“Failing quickly, learning and improving on the previous failures faster means a better end result.”

—Sandia systems engineer Robert Petterborg

“Use of additive manufacturing for both the prototyping and production allowed me to fail and iterate quickly and improve on previous designs, often in less than a week. Failing is a natural part of the design process. Failing quickly, learning, and improving on the previous failures faster means a better end result,” Petterborg said. “I was able to narrow in on the most successful paths and then refine the results to meet the requirements in a shortened timeframe.”

Tapping into Sandia’s knowledge base

Petterborg acknowledged he could not have accomplished designing the new connectors without the help of his colleagues. “At Sandia, we have one of the greatest, deepest knowledge bases of any place in the world,” he said.

Petterborg called on the expertise of machinists across the Labs, Sandia’s Additive Manufacturing Technical Expert Network, the Advanced Materials Processing Lab, and the Additive Manufacturing Lab. He said the input he received from colleagues across the Labs helped him optimize the design of the connector.

Petterborg encouraged other Sandians to take a risk when they see an opportunity.

“Try to do something out of the norm that will benefit your projects. Pursue the solutions that have a high likelihood of success and talk to people with different backgrounds and disciplines,” he said. “Working with the various groups at Sandia, I’ve only encountered people who are excited to help and be involved. It’s as much fun for them as it is to me.”

The team’s accomplishment has been getting a lot of attention. Deputy Labs Director Laura McGill recently demonstrated the connector assembly to congressional staff members.

Robert Petterborg, a Sandia systems engineer, is always up for a challenge. “There is a thrill to digging into something and finding ways to make a system, design, or process better,” Petterborg said. “I have to get out of my comfort zones and challenge myself.”

Petterborg, with the help and input of his colleagues, designed a new cable connector for the W80-4.

“One of the simplified aspects of this project is an easy-to-use solution, which we delivered quickly. There are many things about my design that could be better, but this solution centers on delivering what is needed, when it’s needed, with the resources at hand,” Petterborg said. His design falls in line with Labs Director James Peery’s call for excellence, instead of perfection, to help speed up innovation.

Petterborg said clear and transparent communication with his team and management played a role in the successful design of the new cable connector. He added that poka-yoke was also top of mind. In manufacturing, poka-yoke means creating a solution that anyone can understand, and that is easy to use correctly and impossible to use wrongly.

“I’m fortunate to work with people who are very open to new ideas and different ways to approach complex problems. I think this project is a more prominent or visible result of a culture that regularly innovates with unorthodox solutions that are far more impactful than mine,” Petterborg said. “I have greater fulfillment in my work when I take ownership of not only my projects, but also their impacts to others and our mission.”

As for that thrill of a challenge, it extends beyond work for Petterborg. He installed his own solar array on his house and rebuilt a truck with his wife in their living room while they were college students. “Now I enjoy spending hours painstakingly smoking barbecue and am currently designing a new pit to be able to smoke more,” he said.

Sandia National Laboratories is a multi-mission laboratory operated by National Technology and Engineering Solutions of Sandia LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Honeywell International Inc., for the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration. Sandia Labs has major research and development responsibilities in nuclear deterrence, global security, defense, energy technologies, and economic competitiveness, with main facilities in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Livermore, California.

Kenny Vigil is a writer for Sandia National Laboratories.

An earlier version of this article appeared in Sandia Lab News. Reprinted with permission of Sandia National Laboratories.

Source: