“Even without a surge in reshoring, 2.1 million manufacturing jobs are forecast to go unfilled by 2030.”

— June 2025 Reshoring Survey Report by Harry Moser and Kathy N. Anemogiannis

By Miles Parker, Founder, Parker Group

I have written about, listened to, and encouraged research on reshoring for 25 years. As pressure increases to bring back manufacturing from overseas, I’m excited but skeptical about the effort’s short-term timing and immediate prospects.

It’s not just the politics of large, blanket tariffs that concern me. Factory construction and infrastructure spending, accelerated to meet artificial deadlines, is costly, especially at a time of high interest rates and limited government-supported funding. These costs get reflected in products and services, complicating the value equation.

The fundamentals around quickly using automation to scale up production are also worrying. The cost of productivity investments, as compared to the profit margins industry might achieve in the short run, don’t yet add up. What are customers willing to pay for? And will their ability to buy goods improve?

Harry Moser, founder of the Reshoring Initiative. (Photo courtesy the Reshoring Initiative)

Cost is still king. The labor supply and wage advantage remain overseas. Low-cost, foreign manufacturers are also using automation for speed and quality, just as in the U.S.

The lack of both U.S.-based knowledge workers and assemblers worries me. Overseas expertise is growing by leaps and bounds, from the C-suite to engineering and logistics offices to the factory floor. Western consultants aid in this foreign transformation. Services are America’s main export.

The international and highly integrated nature of supply chains seems irreplaceable. “Build where you sell” also means that factory A in Ohio needs to connect with factory B in Singapore to share designs, technology, and distribute product to markets on-demand as needed, worldwide. It’s very hard to fully protect IP in collaborative environments that are open to better promote efficiency.

Today’s domestic manufacturing crisis, forged from a lack of private vision within individual companies and by too little national attention from government, has left us in poor shape to make a sharp turn with the ship of state.

America doesn’t have the raw industrial assets and human capacity it had entering World War II. Perhaps we as a nation will find our new industrial Golden Age, but it won’t resemble 1930-1944. It will be much more interwoven with best-in-class technologies (and people), wherever they originate. That’s the logical evolution of free trade and competition.

Early Warnings from Intel’s Andy Grove

In July 2010, Andy Grove, retired chairman and then senior advisor at Intel, warned about the exodus of American manufacturing to Asia. In a Businessweek article titled “Andy Grove: How America Can Create Jobs,” Grove addressed the then emerging problem of scaling up U.S. manufacturing as factory investments were instead fleeing overseas. He also spoke about the choice American companies made to pursue fast quarterly profits while their assets and attention turned to foreign development of products. And he spoke to the peril of missing innovation loops when design and manufacturing are separated or even moved wholly overseas.

“As time passed, wages and health-care costs rose in the U.S. China opened up. American companies discovered that they could have their manufacturing and even their engineering done more cheaply overseas. When they did so, margins improved. Management was happy, and so were stockholders. Growth continued, even more profitably. But the job machine began sputtering.

“A new industry needs an effective ecosystem in which technology know-how accumulates, experience builds on experience, and close relationships develop between supplier and customer…we broke the chain of experience that is so important in technological evolution.

“Should we wait and not act on the basis of early indicators? I think that would be a tragic mistake, because the only chance we have to reverse the deterioration is if we act early and decisively.”

Industry, as we know, did not act “early and decisively” on a scale that mattered. But the data and outreach by Grove and others are still there, if followed, to set a course for change.

Geoffrey Boothroyd, Ph.D., and Peter Dewhurst, Ph.D.—winners of a 1991 National Medal of Technology and pioneers in product simplification and early material selection and costing—showed quantitatively that American-made industrial products could potentially compete with Asia on costs.

Harry Moser, president of the Reshoring Initiative, founded in 2010, has emphasized Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) as a path to reshoring and reindustrialization. Moser’s cost analysis considers major areas that comprise the “hidden” costs left out when manufacturers buy by part price.

These areas include “overhead, balance sheet, risks, corporate strategy, and other external and internal business considerations.” The system offers “calculations of 30 cost factors for each source; an accumulation of all costs into cost categories; the TCO for each source; line charts showing each source’s current price and TCO; and a 5-year TCO forecast.” See Impact of Using TCO Instead of Price for a further explanation.

Boothroyd Dewhurst Inc.’s Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DFMA) software, a product labor-cost-reducing methodology in part, teams well with Moser’s TCO. Each have contributed to the accounting landscape needed by U.S. manufacturers to form a credible side-by-side solution to offshoring.

A look at DFMA and TCO shows a solid history of success at understanding and countering costs.

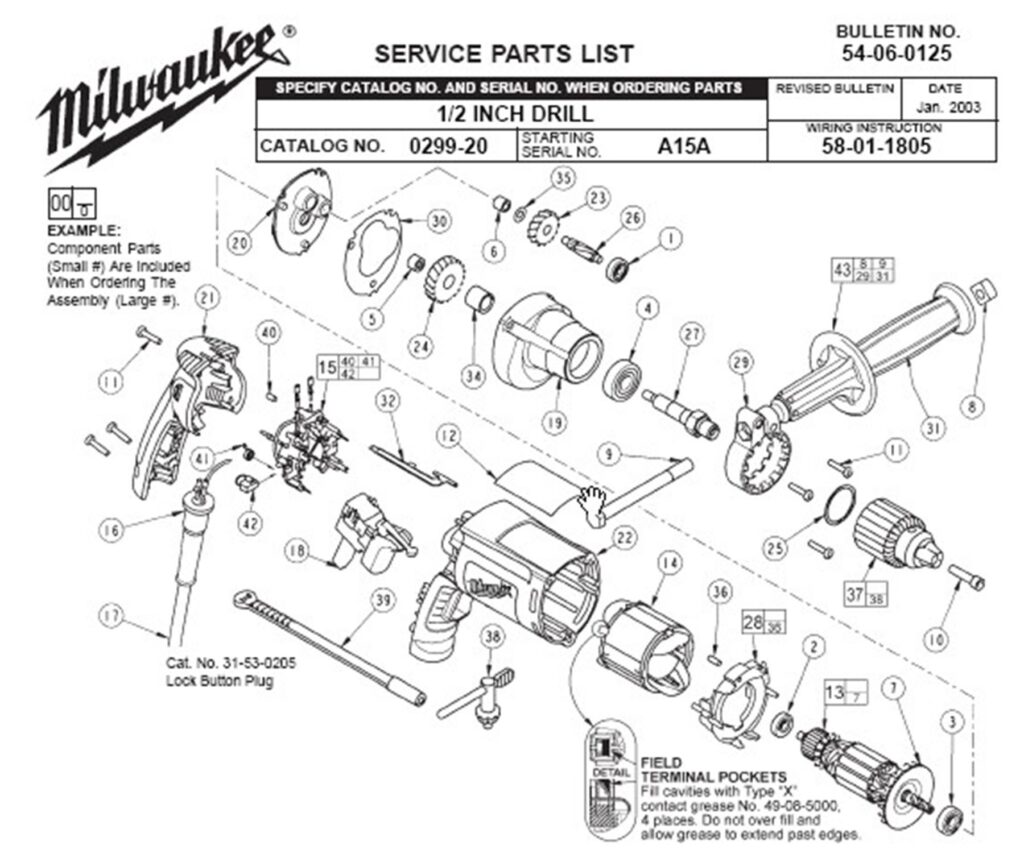

In 2004, Nicholas Dewhurst and David Meeker authored a breakthrough study titled “Improved Product Design Practices Would Make U.S. Manufacturing More Cost Effective—A Case to Consider Before Outsourcing to China.” It offered DFMA-driven domestic redesigns of two American products using their China costs as a baseline. The first product was a power drill from Milwaukee Tool (Image 2a). The second was a major subassembly in a stand-up consumer vacuum cleaner.

Minimum part-count reduction methods and changes in material selection and processes resulted in these “reshoreable” costs below. Even with a numerically conservative and less than fully loaded TCO analysis, the U.S. DFMA power tool design with increased features was only $1.72 more than the original model made in China. Adding overseas risk factors and intangibles, the U.S. DFMA redesign is the best choice.

2a. DFMA® redesigned drill. (Image courtesy Milwaukee Tool/Boothroyd Dewhurst Inc.)

2a. DFMA® redesigned drill. (Image courtesy Milwaukee Tool/Boothroyd Dewhurst Inc.)

| Power Drill

Model |

Location |

Material |

Labor |

Total Cost |

With 24% TCO Adder |

| 0299-20 | China | 61.25 | 0.16 | 61.41 | 76.14 |

| 0299-20a | U.S. | 47.70 | 30.16 | 77.86 |

The DFMA redesign for the vacuum cleaner subassembly (Image 2b) shows a $5.02 saving over the China-produced model. Quoting from the study: “Design analysis indicated that the minimum number of parts required for the product to function was nine. Preliminary design suggestions indicate that reducing the number of parts in the subassembly from 26 to 12 parts is a realistic goal that would result in a cost saving of 27 percent.”

|

Design Variant |

Cost |

With 24% TCO Adder |

| Original design in U.S. | 53.28 | |

| Original design in China | 35.41 | 43.91 |

| DFMA redesign in U.S. | 38.89 |

2b. A consumer vacuum subassembly DFMA® redesign. (Image courtesy Boothroyd Dewhurst Inc.)

What is clear in these two examples from 2004 is that redesign can lower costs when designs are looked at holistically rather than modeled as a collection of individual parts and fasteners.

Encouragingly, many OEMs and contract manufacturers (CMs) intuitively—and by learning from past DFMA examples—follow early part-consolidation practices loosely. Moreover, today’s additive manufacturing (AM) systems are adroit at creating multi-functional single components as envisioned by DFMA.

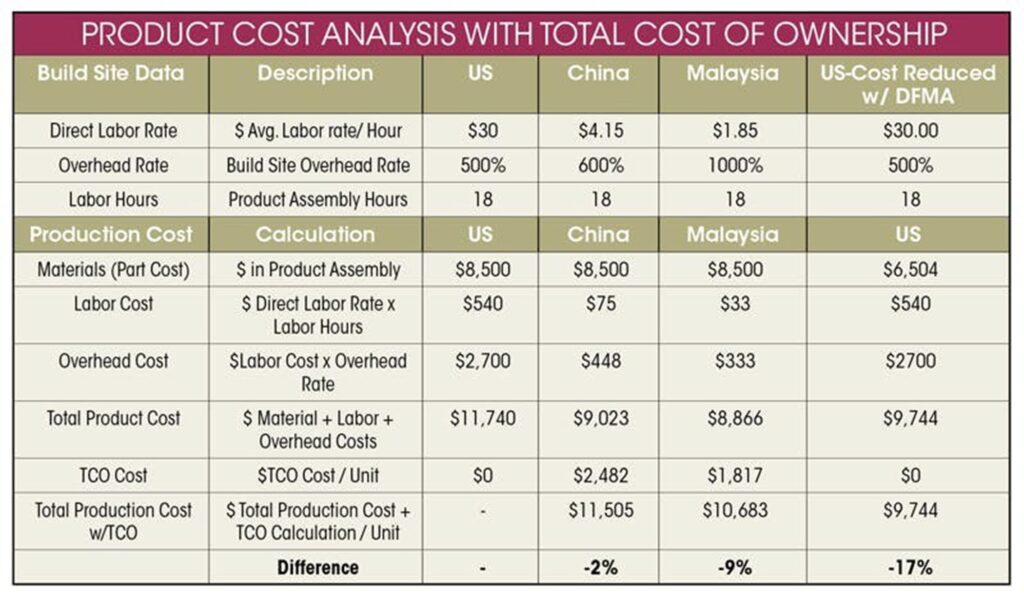

There is another example from 2017 of the use of DFMA and TCO to prove out domestic production. Matt Miles, formerly of Dynisco Instruments, published “Powerful Strategies for Keeping Manufacturing in the U.S,” a very detailed look at costs using a full TCO analysis.

Shown is the total product cost at Dynisco’s overseas facilities after considering TCO and DFMA analysis. (Image courtesy Dynisco Instruments)

Selecting a material-analysis test instrument, one that had low-volume production and over 800 parts, Miles calculated “landed” costs of shipping, insurance, freight, and duties. He then added TCO inputs for the cost of poor quality (COPQ), build-site profit, inventory carrying costs, reoccurring costs (such as travel), and one-time transition costs.

The summary provided by Matt Miles:

“Based on our TCO and DFMA analysis, the decision was made to keep the product at the current U.S. build site. The TCO analysis determined that the year-one cost savings would only be 2 percent or 9 percent lower than the baseline or existing build site. Collectively, two major items factored greatly in the decision. IP transfer was a risk the company was not willing to take from building in another country, and the DFMA analysis showed the potential for greater than a 10 percent cost reduction over the next year. The result: a 17 percent baseline improvement by continuing production in the Midwest—8 percent more cost-effective than Malaysia.”

Moser has his own, more recent TCO-only example of an American reshoring success. Morey Corporation, of Woodridge, Illinois, provides electronic manufacturing services primarily for the commercial vehicle market. Not long ago, the company was about to lose a printed circuit board (PCB) order to China based upon price.

Moser helped with a TCO analysis that Morey then took to its U.S. customer. The cost assessment showed that even though Morey’s domestic PCB price was higher, the domestic TCO was lower—enough to tip the scales. Use of TCO was key to Morey winning a $60 million order.

Implement What’s Been Demonstrated to Work

A constant in achieving manufacturing excellence is use of Lean Principles, Six-Sigma, Value Engineering, and management principles around “waste reduction,” such as those of W. Edwards Deming and his 14 Points. Given the above examples of other important tools, it becomes clear that, central to most of these waste reduction practices should be added DFMA “lean and cost-reduction” methodologies and, confidently, modern TCO accounting. As the nation moves forward on reshoring, we can bolster success by deploying these last two elements within the body of other accepted approaches.

No matter what happens to monetary policy, bonds, treasuries, and tariff adjustments, fundamental practices must be followed in early design and accounting—or no governmental action alone will likely work to improve our trade imbalance. Domestic U.S. manufacturing must compete on cost and efficiency, at least in critical industries.

And Yet: The Challenges of Ramping Up American Production

But a fundamental question emerges: Can the U.S. scale up production and worker training to meet its immediate tariff-driven goals of bringing back overseas manufacturing?

According to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, investment in construction related mostly to the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), and CHIPS Act has created a recent surge in building. This enhanced ability to scale up infrastructure offers hope that such development could continue to increase and support a surge brought about through reshoring.

The recent surge in manufacturing construction spending. (Image courtesy U.S. Census Bureau/Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Could this progress be maintained under the uncertainties and risks to business margins created by fluctuating and historically high tariff rates?

That remains to be seen. The U.S. is still the second largest manufacturer, following China, and has shifted itself away from production of low-cost goods in favor of capital equipment and high-value products, such as aircraft, farm equipment, and electronics. While North American automation, projected to grow at 9.7 percent from 2024 to 2030, can offset some labor needs, engineers in several key categories, such as electrical and civil, could be in short supply.

An Example from Dell Technologies—DFX/DFMA, Scaling, and Labor

Bradley Keup, senior leader across technology, process, and product development (1997-2024) and key technology strategist at Dell from 1997 to 2010, was there at the beginning of the Dell revolution in computers. Before Dell Technologies migrated heavily overseas around 2008-2009, along with other pc-builders, the company established and fostered internally a strong tradition of early conceptual analysis known as Design for “Excellence” (DFX). DFX integrates the disciplines of mechanical, electrical, assembly, quality, manufacturing, analysis, costing, risk assessment, and other lifecycle factors early on to optimize products and process.

Brad Keup served as Dell senior leader across technology, process, and product development until December 2024. (Photo courtesy Brad Keup)

That DFX tradition would well serve companies that are considering reshoring. It puts into focus total costs, total performance of the product—and ways to reduce labor, waste, and capitalization expenditures.

From an article by Keup and Shawn S. Jagodzinski, titled “No New Factories,” Dell management outlined the impact on internal and supply chain production that DFX/DFMA had and could still have today:

“Extended facility life and reduced capital expenditures. Reducing build time and material to be received increases the capacity of our existing factories, extending their life by three to five years. This significantly delays large capital expenditures to erect new state-of-the-art manufacturing facilities to keep up with increased customer demand. It also reduces the capital expenditures needed to increase the productivity of existing facilities and allows Dell to focus its existing labor resources on value-added tasks.

“Dell believes that best-in-class design extends to a consideration of supplier practices. We know that if we design our products so they are easier for our suppliers to manufacture and assemble, we will eventually see savings at Dell. Increased manufacturing throughput, reduced damage rates, higher quality, streamlined logistics, and faster delivery are all outcomes of weaving DFMA into the development cycle.”

Today, Keup looks back at the beginnings: “DFX at Dell started with myself and Doug Dewey working with senior director Jerome Kerns and the Mechanical Engineering team. We started bringing the mechanical and electrical engineers into the factory; I myself worked there for three months. I required every DFX engineering hire to work in the factory for the first month, and at one point we had 20 DFX engineers.

“Then magically, the ‘lights went on.’ There was accountability and an understanding of the whole process at each design step. ‘Hey, we just reduced 20 screws and two minutes of assembly time,’ they said. Well, we dollarized that and put it through our volumes—and it was several million in savings. Throughput doubled and tripled as we improved. Seeing the results, management bought in and our optimization journey accelerated. Suppliers also moved within a mile or two of our Texas facility. We were a model of efficiency and profit.”

With foreign market sales increasing, a build-where-you-sell strategy settled in. Relying on inexpensive foreign labor, as were others then, Dell downsized its PC manufacturing in Texas by 2010, said Keup.

“Our experts dispersed to other companies and fields. There is no DFX/DFMA team per se at Dell today,” he said. “We teach through our quality organization, our Original Design Manufacturer (ODM) partners, and quality team what DFX and DFMA are. Except for critical IP development, most design and manufacturing has been outsourced to ODMs, like what others have done.”

Can applying this kind of thinking bring American production back to the U.S.? Keup believes it can.

“The U.S. can certainly see a resurgence of manufacturing if it’s not an all-in, all-right-now type of decision. Reshoring is not a race or a sprint; it’s a marathon. Re-industrialization must be painstakingly thought out and planned. At the end of the day, profit and loss (P&L) rules. The margins must be made. Investments offset by revenue.”

What does Keup recommend? Here are his main takeaways:

- Educate and secure upper management buy-in on product and process simplification

- Use DFX/DFMA (or near-to methods) to focus the various disciplines on early design involvement

- Train the organization in holistic thinking and identifying product cost-drivers

- Co- or near-locate suppliers

- Reward staff for excellence and teamwork (Dell paid very well)

- Deploy automation and AI to increase factory throughput and efficiency

- Use Total Cost of Ownership

- Be smart; be patient; overcome challenges; trust the DFX process

John Biagioni, president of Lampin Corp., addresses employees on their factory floor. (Photo courtesy Lampin Corp.)

Getting from There to Here

John Biagioni is president of Lampin Corporation, a supplier of precision parts and components for major OEMs in aerospace, telecommunications, robotics, defense, renewable energy, and more. He has played a unique role in applying DFMA and TCO principles over the last two decades. Author of “America’s Offshoring Debacle—Accounting for What Happened,” which appeared in IndustryWeek, Biagioni has been a machinist, executive, and “agnostic” accounting hawk.

Following are Biagioni’s words from a passage in the article:

“I can say with confidence that most manufacturing companies that left the U.S.—with a goal to ship products back—didn’t do much offshore accounting. They based their decisions largely on favorable piece-part costs (from low-detail bids) and on cheap, unburdened foreign-labor rates. What they encountered offshore was an indirect labor burden of five-to-one; constant turnover, training costs, and wage hikes; escalating shipping fees—and an impaired asset base back home. Travel and other expenses were hidden in corporate budgets and were never placed on the piece part that first drew them to foreign soil. Once their overheads started to skyrocket and operating profits plunged, however, those companies felt the ‘real’ math like a stomach virus.

“The lesson: Even if you choose not to practice Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), your company will live or die by it anyway. So better do TCO with the joy of playing a favorite board game, or watch your profits tumble and competitors step ahead.”

To the left is Rick Caponi, Lampin’s director of engineering, with John Biagioni, (center) president of Lampin Corp., and Alex Theisen (right), director of operations for Applied Interactive. (Photo courtesy Lampin Corp.)

Today, Biagoni approaches the topic of reshoring with the same tools and dedicated focus as he did years ago. But the strategic and tactical emphasis at Lampin is different now; it’s on high-end product innovation, agility, skills training, and the productivity growth, and business sustainability possible through an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP). These elements, Biagioni feels, are their keys to success—and a roadmap potentially for other domestic industrial companies.

But there is another interrelated, dual-purpose role at Lampin. It’s that of helping the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) ready for foreign conflicts through the preparation of a better-prepared U.S. industrial base.

That Lampin role, set through both advice and example, holds lessons for American manufacturers. Biagioni is addressing the domestic skilled-labor crisis through deep training and a generous shared-profit incentive (historically, a strong business model). In advising the DoD on using excess American manufacturing capacity, he and others are working to create a stronger, more resilient manufacturing base. This is good for both defense and GDP.

The DoD has created many programs to support and utilize American industry. The Organic Industrial Base (OIB), Defense Digital Engineering Strategy, and Defense Production Act, to name a few. Biagioni and invited industry leaders are working with the National Transportation Defense Association, U.S. Transcom, and National Defense University in Washington, D.C., to help design an improved manufacturing ecosystem for the re-industrialization and mobilization of the industrial base. The effort, said Biagioni, comes in the face of planning for a hypothetical attack from China on Taiwan sometime after December 31, 2026, when the PLA celebrates its 100th anniversary.

Has this kind of war scenario impacted reshoring efforts? Harry Moser’s 2025 survey reveals that 77 percent of OEMs are concerned about an Asian conflict, and 49 percent have identified products to reshore now as insurance against such an event. American industry is preparing, and using TCO in many cases, to stay ahead of this threat.

According to Biagioni, “Mobilization of the industrial base is a deterrent to China. Even if the U.S. achieves a 10 percent renewed industrial capacity that can shift from commercial to military production, China might not make a move on Taiwan.”

Toward this goal, the DoD looks to tap idle and deferred process capacity through a “variable capacity model,” which identifies, networks together, and funds small-to-large shops ranging from CNC to casting specialists.

“Consume existing capability,” said Biagioni. “Some of this emphasis should carry over to reshoring. Not with the same imperative as the DoD, but felt in similar ways.”

A Potential Roadblock: The Skilled-Worker Deficit

With the push from national security concerns, trade deficits, and tariffs, reshoring could indeed take on a new life. The number one barrier, however, according to Moser’s survey, is the crisis in skilled workers. Nearly a half-million manufacturing jobs are currently unfilled. Up to 2.1 million could be unfilled by 2030.

The job flight from manufacturing is due to many factors: an aging demographic, career trends, offshoring, pay dissatisfaction, level of required skills, and regional population shifts and other societal-related causes.

Lampin Corporation and Biagioni are finding their own solutions to workforce recruiting and training. One that, at the least, small- and medium-sized shops that are not already shareholder-owned could implement.

Lampin is a growing company focused on using high-precision, innovative processes. It is demanding, knowledge-oriented work. But they are meeting the recruitment challenge though use of their ESOP.

“We’re finding people that have the right attitude and mechanical leaning—not necessarily the right starting skills—and we’re training them to be machinists,” said Biagioni.

“Profit-sharing is a key motivator and method of employee retention for our company,” he continued. “Lampin contributes approximately 15 percent of employees’ pay into their ESOP retirement plan, while also providing a match contribution on their 401K contributions. This has resulted in more than a million dollars in distributions and diversifications over the previous three years—all to employee owners. In addition to these longer-term incentives, Lampin does quarterly profit sharing determined by the previous quarter’s gross margins.

“Who are our new employees? One worked in a junkyard, another had a degree in criminal science, and another had a custodial background. Where else is the average high-school graduate going to earn that type of a living?

“This is how we are filling our pipeline of talent,” Biagioni said. “That’s a path to hiring for any reshoring surge. Look for people with the right attitude, that want to learn and grow, and create a situation where they can have equity and involvement, without the educational debt.”

Lessons and Insights

The last three decades of computer-aided design (CAD)and manufacturing-software development have seen a great deal of automation take place. Speed and accuracy have dramatically improved. New digital bridges have been created to reach separate yet interdependent disciplines. Products have improved. But I still see some of the same organizational silos and cultural barriers to excellence and innovation that I did in the late 1980s.

Are we able to marshal continuing advances in CAD/CAM/CAE/PLM and take the most obvious past lessons from Deming or Grove or Boothroyd, and use them? When, if not now? Will the chest-high stack of results produced by American companies already using DFX and DFMA matter?

Are the facts of TCO apparent to all those who should be aware of them? Moser has provided the evidence that reshoring can benefit the vast majority of industrial companies that try it—and the software is free. Put TCO alongside standard corporate and operational accounting and labor-cost reducing, product-simplification techniques. See what happens.

Cost is king. Hard fact: The entire world of manufacturing has access to the same productivity software and process equipment, no matter where factories are located. Where can advantages be found? Co- and near-location of the supply chain shaves off costs. That’s an American manufacturing advantage in an American market. Apply TCO and pull everything close that makes sense.

Add-in DFM “should costing” (not price chasing as happened with offshoring to Asia), done with cost transparency and guaranteed margins for suppliers, to spur significant team-based innovation and material and process savings. Make suppliers true design and costing partners. Build internal manufacturing knowledge in that speedy, deadline-busting way.

Embrace digital design automation and related platform “visibility” while remembering that face-to-face team collaboration gives you the “Why’s” and institutional knowledge that can produce exceptionalism and repeatability.

Can’t find and recruit motivated employees? Follow Lampin Corporation’s shared-wealth example, or something similar and authentic. The U.S. does not need to waste resources scaling up for production of low-cost consumer goods. We’ll not win at that. Millions of manufacturing jobs are not going to be created by chasing cheap, commodity goods production. But we probably can—and should—work to fill employment holes for the strategic needs we have in defense, aerospace, heavy industry, computing, and energy.

Tariffs and monetary policy are in flux now. Might we focus on the design and accounting basics? Accepting hidden costs and buying by face-price alone is for the last century. Open collaboration and support from costing software, or AI-analytics, is for this century. Cost is by design. Design then for lower cost.

“I wish the White House would request use of Total Cost of Ownership ahead of sourcing decisions,” Moser said, passionately. “Ask for that one thing of American manufacturers. It would be the cheapest, highest payback, single thing the country could undertake. Just do this math, please.” Harry has a point!

Miles Parker has more than 30 years of experience in writing about technology, particularly design and manufacturing software