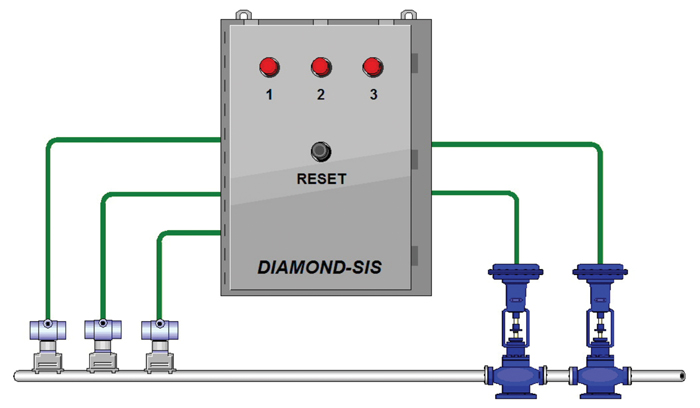

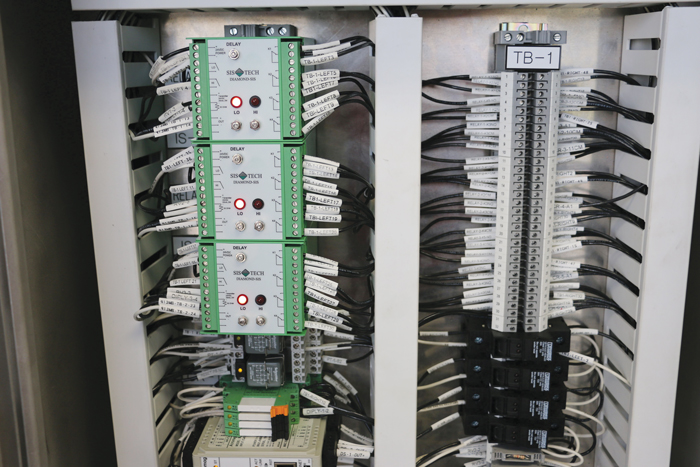

Unlike software-based platforms, hardware systems are physically wired to execute specific safety functions. Voting logic, for instance—two-out-of-three (2oo3) sensors—can be implemented using wiring and trip amplifiers, mounted in a rack room or local panel. (Photo courtesy SIS-Tech)

A growing number of plants are replacing programmable logic controllers with cyber-proof, cost-effective hardware alternatives.

By Greg Rankin

For decades, programmable logic controllers (PLCs) have been the go-to solution for safety systems across refineries, chemical plants, power facilities, and discrete manufacturing facilities. Reliable, flexible, and widely understood, PLCs became the default choice for monitoring, controlling, and responding to critical process conditions. Yet, default doesn’t always mean optimal.

As operating budgets tighten and cybersecurity threats intensify, more facilities are reevaluating whether software-based PLCs are the best fit for safety alarms, interlocks, and safety instrumented systems (SIS). This is particularly true in applications with lower input/output (I/O) requirements. Increasingly, many are turning to simpler, hardware-based alternatives, such as dedicated trip amplifiers and relay-based safety systems, which can offer equivalent protection with fewer drawbacks.

“There’s a perception that PLCs are the only option,” said Tom Crumlish, an instrumentation systems expert at Lenexa, Kansas-based SOR Controls Group. “But in many cases, they’re overkill.”

SOR Controls Group designs and manufactures a broad range of industrial process instrumentation, much of which has traditionally been integrated with PLCs. Lately, however, the company has observed a growing shift as facilities explore alternatives to software-based control.

“When you’re designing safety systems, you want as few variables as possible,” Crumlish explained. “Every layer of software introduces a new set of unknowns.”

Hardwired for safety

With hardware-based systems, you eliminate many of the variables introduced by programmable logic. Since these systems operate without software, they are inherently immune to cyber threats. They also require less infrastructure, can be mounted directly in the field, and continue to function reliably under extreme environmental conditions.

“These systems are designed to be simple,” Crumlish added. “In safety, simplicity is a strength. Every time you remove a layer of complexity, you reduce the chance of failure.”

While PLCs excel in managing complex logic and multi-variable conditions, they come with several notable drawbacks:

The Diamond-SIS is a field-mounted safety system built around a de-energized or fail-safe trip principle which has operated for more than 20 years without a single recorded failure – spurious or dangerous. (Photo courtesy SIS-Tech)

High cost: PLC systems require a substantial upfront investment. Beyond the controllers themselves, costs include I/O modules, human-machine interfaces (HMIs), and ongoing software licensing fees.

Environmental constraints: PLCs must be installed in climate-controlled environments, which can increase capital and maintenance costs.

Complex infrastructure: PLC-based systems typically require extensive cabling and integration, leading to longer project timelines and higher installation costs.

Remote limitations: PLCs are not ideal for remote or standalone locations due to their power requirements and network dependencies.

By contrast, hardware-based systems are “rightsized” for the majority of safety applications, delivering equivalent functionality at a fraction of the cost, often up to 85 percent less than a traditional PLC. Most hardware systems are field-mountable, allowing installation directly adjacent to the equipment they protect. This eliminates many environmental constraints and reduces infrastructure complexity.

These systems are well-suited for both new construction and retrofit projects (brownfield sites) and can also be configured to supplement existing non-certified PLC-based architectures. Common applications include interlocks, permissives, automated overfill prevention, burner management, high-integrity pressure protection systems (HIPPS), and protection for pumps or wellheads.

Rethinking safety and reliability

With constant pressure to maintain uptime, protect assets, and ensure worker safety, reliability is a non-negotiable factor in these industrial environments. Hardware-based safety systems, built on discrete components like relays and trip amplifiers, have been field-proven over decades of real-world use.

An example of such a system is the Diamond-SIS, developed by Houston-based SIS-TECH. It is a field-mounted safety system built around a de-energized or fail-safe trip principle that has operated for more than 20 years without a single recorded failure—spurious or dangerous. When predefined process parameters are exceeded, the system initiates an automatic shutdown, ensuring a fail-safe response without requiring human intervention or network connectivity.

For safety trips, hardware-based systems, such as the Diamond-SIS, are certified to IEC 61508 Safety Integrity Level (SIL) 3 and can be integrated with plant-wide distributed control systems (DCS). This type of configuration enables real-time monitoring while maintaining the inherent reliability of a hardware-based design.

When integrated with the DCS, the hardware-based system can automatically adjust final control elements—such as placing valves into a safe state—acting as a permissive for a controlled, orderly restart once the abnormal condition is resolved. The key advantage lies in combining the dependability of hardware logic with the visibility and coordination of modern control systems.

Industrial safety rewired

Many hardware-based safety systems also excel in environments where space, power, and communications infrastructure are limited. These systems can be deployed in remote areas or satellite facilities that lack climate control or stable power sources.

“They draw very little current, so they can run on solar power without the need for a network connection,” said Crumlish. “We’ve seen these systems operate in extreme heat, high vibration, and electrically noisy environments without issue. That kind of dependability is exactly what safety systems need.”

Unlike software-based platforms, hardware systems are physically wired to execute specific safety functions. Voting logic, for instance—two-out-of-three (2oo3) sensors—can be implemented using wiring and trip amplifiers, mounted in a rack room or local panel. While this approach may appear less flexible, it delivers a higher level of reliability, particularly in safety applications that don’t require frequent reconfiguration.

“Some facilities like to know they can reprogram their systems with a PLC,” said Pete Fuller, an engineer and application manager at SIS-Tech who supports the deployment of hardware-based safety systems. “Our integrated Diamond-SIS is scalable and can be upgraded by simply rewiring or adding components. Modifications to large systems can usually be done in a single day.”

However, Fuller added that for most applications, when a hardware-based system is installed to mitigate a particular hazard, it becomes the foundation for the process’s safe operation and will remain in place, unchanged, for decades.

The manual configuration process for hardware safety systems also eliminates the risk of accidental code changes or remote cyber intrusions. By removing the software layer, hardware-based safety systems reduce exposure to two of the most common failure modes: human error and digital attack.

Common applications for hardware safety instrumented systems include interlocks, permissives, automated overfill prevention, burner management, high-integrity pressure protection systems (HIPPS), and protection for pumps or wellheads. (Photo courtesy SIS-Tech)

Cyber-proof systems

Cybersecurity concerns are becoming a central factor in the move away from PLC-based safety systems. As critical infrastructure faces increasingly sophisticated cyber threats, many operators are reassessing just how much connectivity is truly necessary for safety applications.

“Hardware doesn’t need a firewall,” said Fuller. “There’s no login, no remote access, no software patch updates. It just works. That’s incredibly valuable in safety applications.”

By contrast, even well-secured PLCs are part of a broader network architecture and therefore remain potential targets for intrusion. The 2021 ransomware attack on Colonial Pipeline, which disrupted nearly half of the East Coast’s fuel supply, served as a stark reminder: Even systems with advanced protections can be compromised if they’re connected.

Programmable logic controllers are common in discrete manufacturing, but there are situations similar to those in continuous manufacturing where the required I/O count is relatively low, making a full-scale PLC system more than what’s needed. There are also situations where cybersecurity is paramount.

In these cases, a dedicated hardware-based safety system, such as the Diamond-SIS, can provide a simpler, more cost-effective solution. Below are some specific discrete manufacturing scenarios where such a system can be applied.

Explosive material handling: Industries such as aerospace (solid rocket fuel production), automotive (airbag propellant manufacturing), and electronics (battery manufacturing, especially lithium-ion)

High-pressure forming or testing: Automotive or aerospace forging, composite material curing, and high-pressure hydraulic presses

Specialty chemical integration: Semiconductor fabs, battery assembly lines, and pharmaceutical manufacturing

Defense and aerospace manufacturing: Missile or defense equipment production, satellite component manufacturing, and munitions assembly

Legacy facility modernization: A discrete manufacturing plant with an aging safety infrastructure, where existing safety relays or PLCs are no longer reliable or compliant.

Hardware-based safety systems, built on discrete components like relays and trip amplifiers, have been field-proven over decades of real-world use. (Photo courtesy SIS-Tech)

Hardware-based systems may not be ideal for every situation, however. In applications that require hundreds of sensor inputs, complex sequencing, or advanced data analytics, PLCs offer unparalleled flexibility and scalability. But for many refinery and industrial processes, where the safety logic is straightforward and the I/O count is limited, hardware-based systems present a more targeted, cost-effective, and resilient solution.

As industrial operators continue to modernize their safety protocols, some are choosing to upgrade, not by layering on more complexity, but by simplifying. In industries where uptime, safety, and security are non-negotiable, hardware-based safety systems are proving that less complexity can deliver more confidence and greater protection when it matters most.

Greg Rankin is a Houston-based freelance writer with more than 20 years of experience writing about cybersecurity, technology, and the defense industrial base.