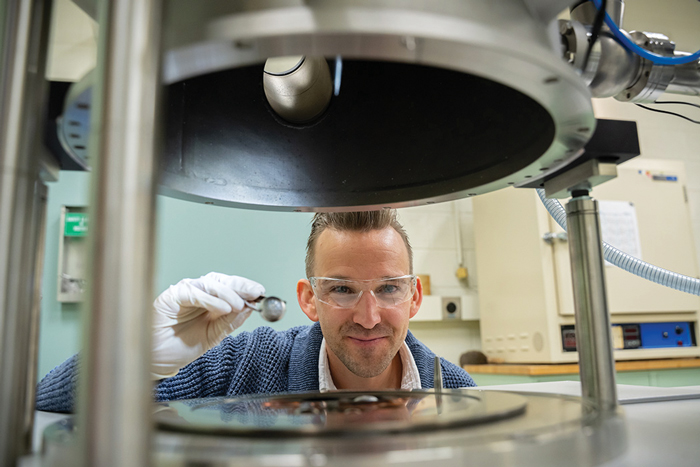

NIST researcher Andrew Iams in the lab. (Image courtesy M. King/NIST)

Engineers at NIST are studying how to make high-quality steel out of the raw materials we currently have available in the U.S.

By Andrew Iams

I grew up outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, known as “The Steel City.” Although no longer the center of steel or heavy manufacturing in America, this past remains a proud part of the city’s identity.

Like many Pittsburghers, my family’s story is tied to this industrial legacy. My relatives immigrated there in search of work and found it at Westinghouse, a manufacturing giant of its day. I followed in their footsteps, becoming the fourth generation to work there. And like my ancestors before me, I supported manufacturing.

Throughout my time in Pittsburgh, I witnessed the decline of steel and associated industries, which hurt my hometown. As jobs were lost, families and communities struggled.

Both my time in Pittsburgh and industry experiences shaped the path that eventually led me to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). I found materials science and the opportunity to research a topic deeply rooted in my hometown: steel.

Now, I am contributing to innovations in the lab that support a vibrant and resilient domestic steel industry. This work is deeply personal, rooted in the industrial legacy of the community where I grew up. I hope that this work will lead to future opportunities, not just in Pittsburgh but in manufacturing towns across the country.

Rethinking Ironmaking for the 21st Century

Iron is a key ingredient in steelmaking. It is often made within a blast furnace, where iron ore is reduced to molten iron using carbon monoxide gas. This reducing gas is produced from burning a carbon source derived from coal, known as coke.

Interestingly, the blast furnace iron production method today isn’t so different from ones developed thousands of years ago. The process uses similar chemical reactions that were used in ancient furnaces in operation around 1,000 BCE. These time-tested processes are ripe for innovation.

At NIST, we are researching new approaches to ironmaking, focusing on processes known as direct reduction. Unlike traditional blast furnace methods that use carbon monoxide gas derived from coke, direct reduction uses gases, such as pure hydrogen or reformed natural gas, to reduce iron ore to iron.

When pure hydrogen is used as the reducing gas in these processes, the byproduct is water vapor. In addition to pure hydrogen, reformed natural gas can also be used. This yields a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, both serving as reducing agents. Advancing these processes offers opportunities to use the country’s abundant domestic natural gas reserves. It also strengthens the U.S. ironmaking supply chain, which has shifted overseas in recent decades.

NIST researcher Andrew Iams is researching new approaches to ironmaking. (Photo courtesy M. King/NIST)

While direct reduction ironmaking shows great promise, many technical challenges limit widespread industrial adoption. One of these challenges is related to iron ore quality.

Direct reduction ironmaking requires a high-quality iron ore, but much of this domestic resource has already been mined. The lower-quality iron ore that remains contains more impurities, which could result in lower-quality steel if we don’t learn how to work with it. That’s exactly what we’re working to do here at NIST, studying how to make high-quality steel out of the raw materials we currently have available in the United States

We are specifically trying to understand how these impurities impact the chemical reaction as the iron ore transforms into iron. We use a range of tools to evaluate this, including a specialized microscope that can magnify material over one million times. This allows us to observe the arrangement of atoms. This measurement technique provides a fundamental understanding of the role of impurities and how we might mitigate their effects. If we can do this, manufacturers might be able to use lower-grade iron ores and still get high-quality steel as a result, which would be ideal for domestic steel manufacturers.

The Role of Recycling in Modern Steel

Modern steelmaking depends not only on how we produce iron, but also how effectively we recycle materials.

Much of steelmaking in the U.S. uses recycled scrap metal as input material. In addition to iron, this scrap is melted down in an electric arc furnace. Steel is 100 percent recyclable and has one of the highest recycling rates of any material, meaning steel produced today could have previously been in cars, buildings, or appliances.

However, the steel industry is faced with a challenge in sourcing scrap. The high demand for steel is depleting high-quality scrap, pushing the industry to use lower-quality scrap, which often contains impurities. These impurities can carry over into newly produced steel, weakening its performance.

This concept is like recycling glass or plastic: The cleaner the material, the better the recycling outcome. Glass free from metal lid rings or plastic free from food residue is far more likely to be turned into high-quality products when recycled. The same idea applies to scrap steel.

We are exploring multiple solutions to address the challenges of low-quality metal scrap. One path is to improve recycling technologies to sort scrap more effectively and remove contamination. Another strategy is to design novel metal alloys that are more tolerant of impurities.

A combination of solutions will likely be required.

From Measurement to Manufacturing: NIST’s Impact

I work with a team of materials scientists who bring significant experience and deep technical knowledge to some of the toughest challenges facing U.S. industries. What makes our work so impactful is the focus on precision. NIST’s core strength is measuring things precisely. This is key to establishing the technical basis for industrial standards or understanding and improving materials, such as iron and steel.

But we don’t work alone. Close collaborations with industry ensure that laboratory breakthroughs transition to industry successes, strengthening manufacturing, revitalizing supply chains, and enhancing our national resilience.

My hope is that scientific precision and industrial strength will help to create future opportunities in the communities that built America, similar to the one I grew up in.

About the author

Andrew D. Iams is a materials research engineer at NIST, where he investigates microstructural characteristics of a range of materials (metals, ceramics, glasses, and polymers). Before working at NIST, he was a senior engineer at Westinghouse Electric Company – Material Center of Excellence. Iams is from the steel city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and holds a Ph.D. in materials science and engineering from the Pennsylvania State University.

About NIST

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) was founded in 1901 and is now part of the U.S. Department of Commerce. It is one of the nation’s oldest physical science laboratories. Congress established the agency to remove a major challenge to U.S. industrial competitiveness at the time—a second-rate measurement infrastructure that lagged behind the capabilities of the United Kingdom, Germany, and other economic rivals.

From the smart electric power grid and electronic health records to atomic clocks, advanced nanomaterials, and computer chips, innumerable products and services rely in some way on technology, measurement, and standards provided by the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Today, NIST measurements support the smallest of technologies to the largest and most complex of human-made creations—from nanoscale devices so tiny that tens of thousands can fit on the end of a single human hair, up to earthquake-resistant skyscrapers and global communication networks.

The mission of NIST is to promote U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness by advancing measurement science, standards, and technology in ways that enhance economic security and improve our quality of life.

Source: NIST